|

|

1970

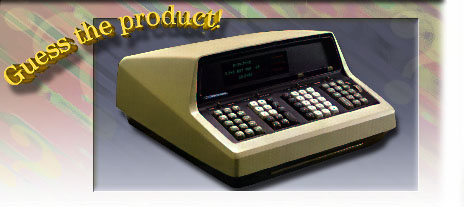

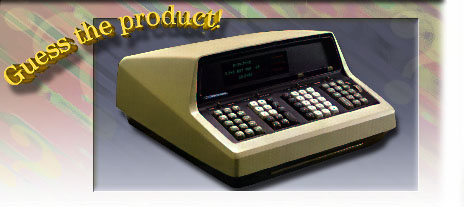

The HP9100A/B Scientific Calculator (Cont'd)

AICS Research's Text

The Remote Environmental Telemetry System

In 1970, we took the same HP9100 calculator, repackaged it,

and significantly upgraded its

responsibilities. Not only did it continue to control the eight environmental

control chambers, it also became the centerpiece of a remote environmental

telemetry system that stretched 200 miles from the

Lincoln National Forest

in the north to the

Plant Science Center

south of Las Cruces, New Mexico.

AICS Research's Text

The Remote Environmental Telemetry System

In 1970, we took the same HP9100 calculator, repackaged it,

and significantly upgraded its

responsibilities. Not only did it continue to control the eight environmental

control chambers, it also became the centerpiece of a remote environmental

telemetry system that stretched 200 miles from the

Lincoln National Forest

in the north to the

Plant Science Center

south of Las Cruces, New Mexico.

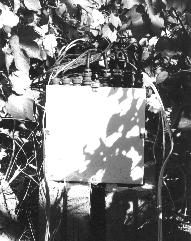

Remote telemetry stations were designed and constructed

so that up to 16 sensors per station

could transmit abiotic (weather) information back to the HP9100A calculator. The

two principal research efforts at the time concerned phytophagous cotton

insects and bark beetle infestations in the Lincoln Forest.

In both instances, sensors were placed at various heights in the plant canopies

to accurately record their various microclimates throughout the year, the only

difference being that the top of the cotton canopy was approximately four feet

tall at its highest and the pine forest canopy was 70 to 100 feet tall. The white

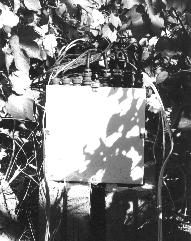

container in the right photograph was a surplus missile warhead container that

we obtained from White Sands Missile Range. These lockable

containers proved necessary

to protect the telemetry stations from hunters.

Remote telemetry stations were designed and constructed

so that up to 16 sensors per station

could transmit abiotic (weather) information back to the HP9100A calculator. The

two principal research efforts at the time concerned phytophagous cotton

insects and bark beetle infestations in the Lincoln Forest.

In both instances, sensors were placed at various heights in the plant canopies

to accurately record their various microclimates throughout the year, the only

difference being that the top of the cotton canopy was approximately four feet

tall at its highest and the pine forest canopy was 70 to 100 feet tall. The white

container in the right photograph was a surplus missile warhead container that

we obtained from White Sands Missile Range. These lockable

containers proved necessary

to protect the telemetry stations from hunters.

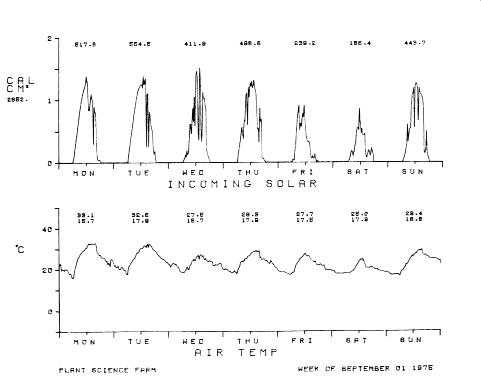

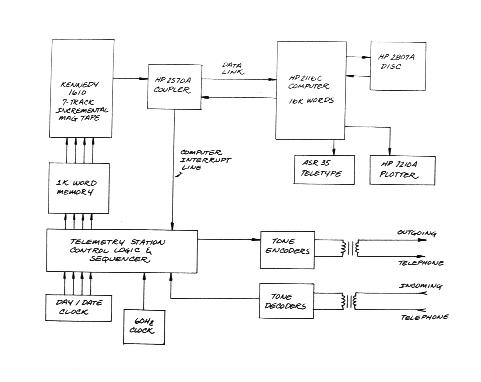

The data transmitted back to the lab was recorded and passed on to the HP2116C

computer for plotting and numerical integration. Insects respond to a wide variety

of abiotic signals, but generally in a summed fashion such that total

heat input or duration of daylight trigger fundamental physiological changes

in them. Handling the insects was generally performed

during their "night" period, in red light, which is invisible to them, in order

to minimize resetting their natural clocks.

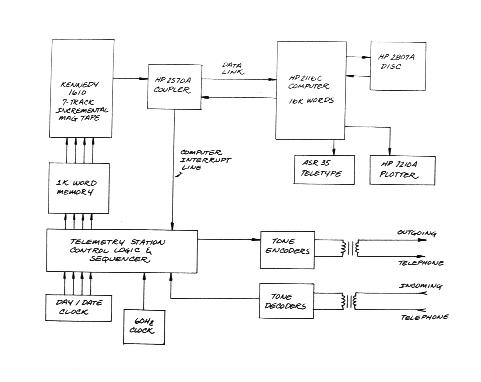

The data returned to the lab was not only recorded by the HP9100

calculator, but could also be sent simultaneously to one or more of the

environmental chambers so that the external environment could be recreated

within the chambers themselves. Every few seconds, the

HP9100 readjusted the settings in the eight environmental control chambers.

Interleaved with this activity, once every few minutes, the HP9100 calculator

would query each of the remote telemetry stations.

The data transmitted back to the lab was recorded and passed on to the HP2116C

computer for plotting and numerical integration. Insects respond to a wide variety

of abiotic signals, but generally in a summed fashion such that total

heat input or duration of daylight trigger fundamental physiological changes

in them. Handling the insects was generally performed

during their "night" period, in red light, which is invisible to them, in order

to minimize resetting their natural clocks.

The data returned to the lab was not only recorded by the HP9100

calculator, but could also be sent simultaneously to one or more of the

environmental chambers so that the external environment could be recreated

within the chambers themselves. Every few seconds, the

HP9100 readjusted the settings in the eight environmental control chambers.

Interleaved with this activity, once every few minutes, the HP9100 calculator

would query each of the remote telemetry stations.

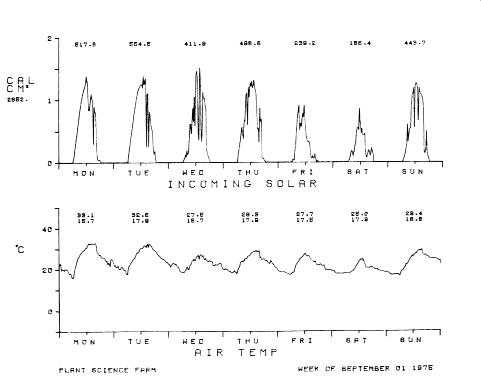

Each remote telemetry station generated eight pages of plotter output per week,

if all 16 sensors were active. The qualities recorded were

most generally soil, air, bark and leaf

temperatures, humidities, soil water tension, rain, wind speed and wind

direction, although any physical quality could have been measured. Indeed, we

were just beginning to measure electrical field strength and electron density,

both of which were suspected of being sensible by our insects, when the

project came to an end in 1976.

Each remote telemetry station generated eight pages of plotter output per week,

if all 16 sensors were active. The qualities recorded were

most generally soil, air, bark and leaf

temperatures, humidities, soil water tension, rain, wind speed and wind

direction, although any physical quality could have been measured. Indeed, we

were just beginning to measure electrical field strength and electron density,

both of which were suspected of being sensible by our insects, when the

project came to an end in 1976.

Although it's difficult to remember nowadays, standard communication speeds

for teletypes were 110 baud. And 1K of memory was actually considered

a fair amount of writable store. "High-speed" 300 baud modems were just beginning

to arrive in the late 1960s, but you couldn't connect a non-Bell System modem

to your telephone lines at the time.

However, in our case, the Bell modems that were available

weren't usable. They drew far too much power and wouldn't fit in our

size constraints.

So we built our own modems from scratch, designing the UARTs (using

TTL flip-flops and NAND gates) and tone decoders, and having

them integrated into the remote telemetry station circuit boards, all of

which were hand wire-wrapped by the wildlife and biology students.

In order to connect these "modems" to the telephone network we had to undergo a

reasonably rigorous certification process by Mountain Bell to guarantee that

the modems met all Bell standards. In spite of the pro forma procedures

associated with this certification, the local Bell people were always very

helpful. But then again, we were paying them a great deal of money each month.

Although it's difficult to remember nowadays, standard communication speeds

for teletypes were 110 baud. And 1K of memory was actually considered

a fair amount of writable store. "High-speed" 300 baud modems were just beginning

to arrive in the late 1960s, but you couldn't connect a non-Bell System modem

to your telephone lines at the time.

However, in our case, the Bell modems that were available

weren't usable. They drew far too much power and wouldn't fit in our

size constraints.

So we built our own modems from scratch, designing the UARTs (using

TTL flip-flops and NAND gates) and tone decoders, and having

them integrated into the remote telemetry station circuit boards, all of

which were hand wire-wrapped by the wildlife and biology students.

In order to connect these "modems" to the telephone network we had to undergo a

reasonably rigorous certification process by Mountain Bell to guarantee that

the modems met all Bell standards. In spite of the pro forma procedures

associated with this certification, the local Bell people were always very

helpful. But then again, we were paying them a great deal of money each month.

|