|

|

1968

HP's Text

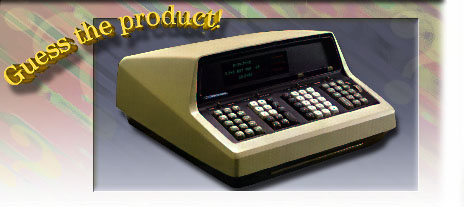

The HP9100A/B Scientific Calculator

The world's first programmable scientific desktop calculator, the HP 9100A

could add, subtract, multiply, divide, take square roots with 10-digit

accuracy, compute logarithms and compute the full range of trigonometric

functions in all quadrants in either degrees or radians. In a unit the size of a

typewriter, with built-in, read-only memory that stored calculating and display

routines, and the ability to perform floating-point calculations, the HP 9100A

could run programs recorded on wallet-size magnetic cards.

AICS Research's Text

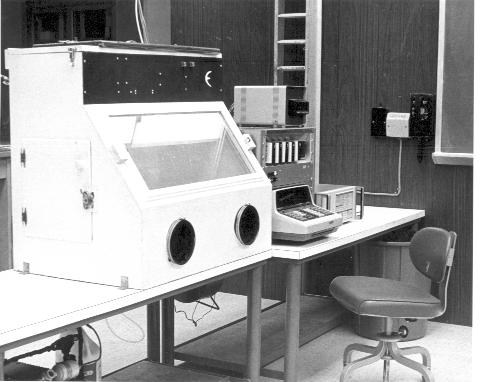

The Environmental Chamber Controller

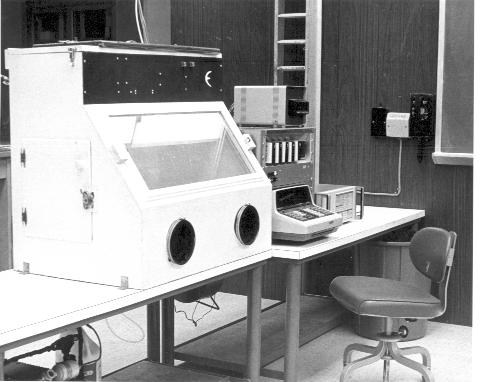

In 1968, we purchased a HP9100 Calculator as soon as one became available.

And then we performed a lobotomy on it. The case of the HP9100 was cast

aluminum, which we very carefully sawed off.

The HP9100 was built prior to the use of integrated

circuits, thus every transistor in the HP9100

was a discrete device and the "ROM" was composed of four

stacked boards that completely consumed the base of the calculator. The logic of

the ROM was created through the use of

a resistor/diode matrix (not unlike the display/keyboard computer

that was on board the Apollo spacecraft that was flying to the Moon at the

same time, although that computer was completely encased in poured plexiglass

for mechanical rigidity).

We opened the calculator up in order to use it for a purpose for which it was

never designed: an environmental chamber controller. To do this, various signals

had to be intercepted from the circuit boards and converted into then-new

TTL logic levels. And an 8-bit, sharable bus structure was designed to allow

a serially sharable talker/many listener protocol to transmit the calculator's

programmed commands to up to eight environmental control chambers simultaneously

and listen to their responses.

Our HP representatives at the time were Norm Matlock, Ralph Kotowski, Jim Kemp,

and Bill Little. Norm was excited enough about the novel use of the HP9100 that he

convinced a group of HP engineers from the Colorado Springs Division to fly

down and see what had been done. Eventually, three groups of HP engineers visited

the lab at separate times and asked if they could copy the design,

although it was nothing that they wouldn't have devised on their own.

With some modification, HP later

released the design as an internal standard and called it HP-IB, which was

later certified to become IEEE-488.

AICS Research's Text

The Environmental Chamber Controller

In 1968, we purchased a HP9100 Calculator as soon as one became available.

And then we performed a lobotomy on it. The case of the HP9100 was cast

aluminum, which we very carefully sawed off.

The HP9100 was built prior to the use of integrated

circuits, thus every transistor in the HP9100

was a discrete device and the "ROM" was composed of four

stacked boards that completely consumed the base of the calculator. The logic of

the ROM was created through the use of

a resistor/diode matrix (not unlike the display/keyboard computer

that was on board the Apollo spacecraft that was flying to the Moon at the

same time, although that computer was completely encased in poured plexiglass

for mechanical rigidity).

We opened the calculator up in order to use it for a purpose for which it was

never designed: an environmental chamber controller. To do this, various signals

had to be intercepted from the circuit boards and converted into then-new

TTL logic levels. And an 8-bit, sharable bus structure was designed to allow

a serially sharable talker/many listener protocol to transmit the calculator's

programmed commands to up to eight environmental control chambers simultaneously

and listen to their responses.

Our HP representatives at the time were Norm Matlock, Ralph Kotowski, Jim Kemp,

and Bill Little. Norm was excited enough about the novel use of the HP9100 that he

convinced a group of HP engineers from the Colorado Springs Division to fly

down and see what had been done. Eventually, three groups of HP engineers visited

the lab at separate times and asked if they could copy the design,

although it was nothing that they wouldn't have devised on their own.

With some modification, HP later

released the design as an internal standard and called it HP-IB, which was

later certified to become IEEE-488.

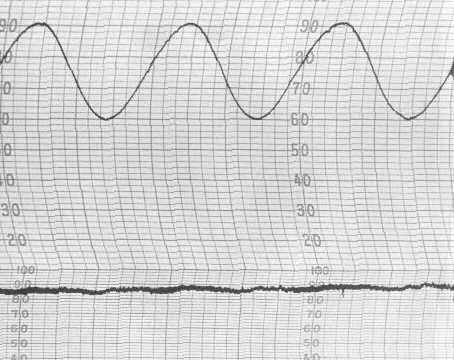

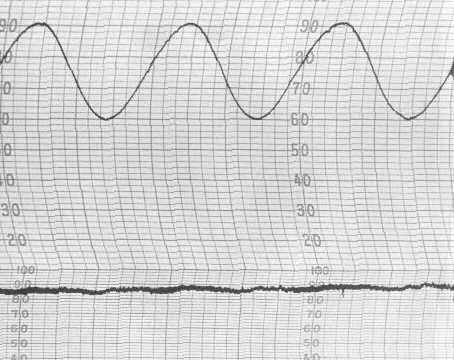

The level of environmental control that we could obtain within the chambers

using the HP9100 calculator was impressive. The graph above is the output

of a mechanical hydrothermograph. This specific data

was an early test run to demonstrate

the chambers' capabilites over a two-week test run (only three days are

visible in the photo above).

Insects are extremely elaborate behavorial machines, more elaborate than the

most complex mechanical machine ever built by humans.

Much of their behavior is driven by

abiotic environmental

stimuli (temperature, humidity, daylength, light levels, etc.). These chambers

were designed to simulate those stimuli in an effort to tease apart the factors

that promote the onset of such key behaviors such as ovipositional (egg-laying)

rates.

In the graph above, the temperature was commanded to cycle sinusoidally

precisely

plus and minus 15 degrees Farenheit from the room's ambient 75 degrees while

maintaining a relative humidity (atmospheric water saturation percentage)

fixed at 85%. As you can see, control was nearly absolute. This level of

precision control

was accomplished by running small multi-stage refridgeration units (one

per chamber) in opposition

to air and water heaters. Although the technique was energy-expensive,

the level of control necessary to the task demanded this design.

The sensors in each of the chambers were idiosyncratic, thus the HP9100

maintained a different calibration table for each temperature and humidity

sensor in the chamber field. But it was the ease of generating elaborate

polynomial equations using the HP9100's intrinsic scientific calculation

capabilities

for complex curve-fittings that made the HP9100 such an ideal controller.

Every calculator manufactured from HP following the 9100

incorporated a controller interface and became more and more

elaborate in its capacities to control instruments. The later

calculators incorporated a very

fine BASIC language as their operating system. Nonetheless, for years following

the HP9100, when HP advertised their new controller calculators, the example

they always used in their advertisements was that of controlling environmental

control chambers.

The level of environmental control that we could obtain within the chambers

using the HP9100 calculator was impressive. The graph above is the output

of a mechanical hydrothermograph. This specific data

was an early test run to demonstrate

the chambers' capabilites over a two-week test run (only three days are

visible in the photo above).

Insects are extremely elaborate behavorial machines, more elaborate than the

most complex mechanical machine ever built by humans.

Much of their behavior is driven by

abiotic environmental

stimuli (temperature, humidity, daylength, light levels, etc.). These chambers

were designed to simulate those stimuli in an effort to tease apart the factors

that promote the onset of such key behaviors such as ovipositional (egg-laying)

rates.

In the graph above, the temperature was commanded to cycle sinusoidally

precisely

plus and minus 15 degrees Farenheit from the room's ambient 75 degrees while

maintaining a relative humidity (atmospheric water saturation percentage)

fixed at 85%. As you can see, control was nearly absolute. This level of

precision control

was accomplished by running small multi-stage refridgeration units (one

per chamber) in opposition

to air and water heaters. Although the technique was energy-expensive,

the level of control necessary to the task demanded this design.

The sensors in each of the chambers were idiosyncratic, thus the HP9100

maintained a different calibration table for each temperature and humidity

sensor in the chamber field. But it was the ease of generating elaborate

polynomial equations using the HP9100's intrinsic scientific calculation

capabilities

for complex curve-fittings that made the HP9100 such an ideal controller.

Every calculator manufactured from HP following the 9100

incorporated a controller interface and became more and more

elaborate in its capacities to control instruments. The later

calculators incorporated a very

fine BASIC language as their operating system. Nonetheless, for years following

the HP9100, when HP advertised their new controller calculators, the example

they always used in their advertisements was that of controlling environmental

control chambers.

|